Chapter 19 Study steps

Chapter leads: Sara Dempster & Martijn Schuemie

Here we aim to provide a general step-by-step guide to the design and implementation of an observational study with the OHDSI tools. We will break out each stage of the study process and then describe steps generically and in some cases discuss specific aspects of the main study types (1) characterization, (2) population level estimation (PLE), and (3) patient level prediction (PLP) described in earlier chapters of the Book of OHDSI. To do so, we will synthesize many elements discussed in the previous chapters in a way that is accessible for the beginner. At the same time, this chapter can stand alone for a reader who wants practical high-level explanations with options to pursue more in-depth materials in other chapters as needed. Finally, we will illustrate throughout with a few key examples.

In addition, we will summarize guidelines and best practices for observational studies as recommended by the OHDSI community. Some principles that we will discuss are generic and shared with best practice recommendations found in many other guidelines for observational research while other recommended processes are more specific to the OHDSI framework. We will therefore highlight where OHDSI-specific approaches are enabled by the OHDSI tool stack.

Throughout the chapter, we assume that an infrastructure of OHDSI tools, R and SQL are available to the reader and therefore we do not discuss any aspects of setting up this infrastructure in this chapter (see Chapters 8 and 9 for guidance). We also assume our reader is interested in running a study primarily on data at their own site using a database in OMOP CDM (for OMOP ETL, see Chapter 6). However, we emphasize that once a study package is prepared as discussed below, it can in principle be distributed and executed at other sites. Additional considerations specific to running OHDSI network studies, including organizational and technical details, are discussed in detail in Chapter 20.

19.1 General Best Practice Guidelines

19.1.1 Observational Study Definition

An observational study is a study where, by definition, patients are simply observed and no attempt is made to intervene in the treatment of specific patients. Sometimes, observational data are collected for a specific purpose as in a registry study, but in many cases, these data are collected for some purpose other than the specific study question at hand. Common examples of the latter type of data are Electronic Health Records (EHRs) or administrative claims data. Observational studies are often referred to as secondary use of data. A fundamental guiding principle for performing any observational study is to explicitly describe one’s research question and fully specify the approach in advance of executing a study. In this regard, an observational study should be no different than a clinical trial, except that in a clinical trial, patients are recruited and followed in time for the primary purpose of answering a specific question, usually about the efficacy and/or safety of a therapeutic intervention. There are many ways in which the analysis methods employed in observational studies are different than those used in clinical trials. Most notably, the lack of randomization in PLE observational studies requires approaches to control confounding if the goal is to draw causal inferences (see Chapters 12 and 18 for detailed discussion of OHDSI-supported study designs and methods for PLE such as methods to remove observed confounding by balancing populations across many characteristics).

19.1.2 Pre-Specification of Study Design

Pre-specification of an observational study design and parameters is critical to avoid introducing further bias by subconsciously or consciously evolving one’s approach to achieve a desired result, sometimes referred to as p-hacking. The temptation not to fully specify the study details in advance is greater with secondary use of data than primary use because these data, such as EHR and claims, sometimes give the researcher a sense of infinite possibilities, leading to a meandering line of inquiry. The key then is to still impose the rigorous structure of scientific inquiry despite the apparent easy availability of pre-existing data. The principle of pre-specification is especially important in PLE or PLP to ensure rigorous or reproducible results as these findings may ultimately inform clinical practice or regulatory decisions. Even in the case of a characterization study being conducted purely for exploratory reasons, it is still preferable to have a well-specified plan. Otherwise an evolving study design and analysis process will become unwieldy to document, explain and reproduce.

19.1.3 Protocol

An observational study plan should be documented in the form of a protocol created prior to executing a study. At a minimum, a protocol describes the primary study question, the approach, and metrics that will be used to answer the question. The study population should be described to a level of detail such that the study population may be fully reproduced by others. In addition, all methods or statistical procedures and the form of expected study results such as metrics, tables and graphs should be described. Often, a protocol will also describe a set of pre-analyses designed to assess the feasibility or statistical power of the study. Furthermore, protocols may contain descriptions of variations on the primary study question referred to as sensitivity analyses. Sensitivity analyses are designed to evaluate the potential impact of study design choices on the overall study findings and should be described in advance whenever possible. Sometimes unanticipated issues arise that may necessitate a protocol amendment after a protocol is completed. If this becomes necessary, it is critical to document the change and the reasons for the change in the protocol itself. Particularly in the case of PLE or PLP, a completed study protocol will ideally be recorded in an independent platform (such as clinicaltrials.gov or OHDSI’s studyProtocols sandbox) where its versions and any amendments can be tracked independently with timestamps. It is also often the case that your institution or the owner of the data source will require the opportunity to review and approve your protocol prior to study execution.

19.1.4 Standardized Analyses

A unique advantage of OHDSI is the ways in which the tools support planning, documentation and reporting by recognizing that there are really a few main classes of questions that are asked repeatedly in observational studies (Chapters 2, 7, 11, 12, 13), thereby streamlining the protocol development and study implementation process through automation of aspects that are repeated. Many of the tools are designed to parameterize a few study designs or metrics that address a majority of use cases that will be encountered. For example, the researchers specify their study populations and a few additional parameters and perform numerous comparative studies iterating over different drugs and/or outcomes. If a researcher’s questions fit into the general template, there are ways to automate the generation of many of the basic descriptions of study populations and other parameters required for the protocol. Historically, these approaches were motivated out of the OMOP experiments which sought to evaluate how well observational study designs were able to reproduce known causal links between drugs and adverse events by iterating over many different study designs and parameters.

The OHDSI approach supports the inclusion of feasibility and study diagnostics within the protocol by again enabling these steps to be performed relatively simply within a common framework and tools (see section 19.2.4 below).

19.1.5 Study Packages

Another motivation for standardized templates and designs is that even when a researcher thinks a study is described in complete detail in the form of a protocol, there may be elements that are not actually sufficiently specified to generate the full computer code to execute the study. A related fundamental principle which is enabled by the OHDSI framework is to generate a completely traceable and reproducible process documented in the form of computer code, often referred to as a “study package.” OHDSI best practice is to record such a study package in the git environment. This study package contains all parameters and versioning stamps for the code base. As mentioned previously, observational studies are often asking questions with potential to impact public health decisions and policy. Therefore, before acting on any findings, they should ideally be replicated in multiple settings by different researchers. The only way to achieve such a goal is for every detail required to fully reproduce a study to be mapped out explicitly and not left to guesswork or misinterpretation. To support this best practice, the OHDSI tools are designed to aid in the translation from a protocol in the form of a written document into a computer or machine-readable study package. One tradeoff of this framework is that not every use case or customized analysis can easily be addressed with the existing OHDSI tools. As the community grows and evolves, however, more functionality to address a larger array of use cases is being added. Anyone involved in the community may raise suggestions for new functionality driven by a novel use case.

19.1.6 The Data Underlying the CDM

OHDSI studies are premised on observational databases being translated into the OMOP common data model (CDM). All OHDSI tools and downstream analytics steps make an assumption that the data representation conforms to the specifications of the CDM (see Chapter 4). It is therefore also critical that the ETL process (see Chapter 6) for doing so is well-documented for your specific data sources as this process may introduce artifacts or differences between databases at different sites. The purpose of the OMOP CDM is to move in the direction of reducing site specific data representation, but this is far from a perfect process and still remains a challenging area that the community seeks to improve. It therefore remains critical when executing studies to collaborate with individuals at your site, or at external sites when executing network studies, who are intimately familiar with any source data that has been transformed into the OMOP CDM.

In addition to the CDM, the OMOP standardized vocabulary system (Chapter 5) is also a critical component of working with the OHDSI framework to obtain interoperability across diverse data sources. The standardized vocabulary seeks to define a set of standard concepts within each vocabulary domain to which all other source vocabulary systems are mapped. In this way, two different databases which use a different source vocabulary system for drugs, diagnoses or procedures will be comparable when transformed into the CDM. The OMOP vocabularies also contain hierarchies which are useful in identifying the appropriate codes for a particular cohort definition. Again, it is recommended best practice to implement the vocabulary mappings and use the codes of OMOP standardized vocabularies in downstream queries in order to gain the full benefits of ETLing your database into the OMOP CDM and using the OMOP vocabulary.

19.2 Study Steps in Detail

19.2.1 Define Question

The first step is to translate your research interest into a precise question that can be addressed with an observational study. Let’s say that you are a clinical diabetes researcher and you want to investigate the quality of care being delivered to patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). You can break this bigger objective down into much more specific questions that fall into one of the three types of questions first described in Chapter 7.

In a characterization study, one could ask, “do prescribing practices conform to what is currently recommended for those with mild T2DM versus those with severe T2DM in a given healthcare environment?” This question does not ask a causal question about the effectiveness of any given treatment relative to another; it is simply characterizing prescribing practices in your database relative to a set of existing clinical guidelines.

Maybe you are also skeptical whether or not the prescribing guidelines for T2DM treatment are best for a particular subset of patients such as those with both a diagnosis of T2DM and heart disease. This line of inquiry can be translated into a PLE study. Specifically, you can ask a question about the comparative effectiveness of 2 different T2DM drug classes in preventing cardiovascular events, such as heart failure. You might design a study to examine the relative risks of hospitalization for heart failure in two separate cohorts of patients taking the different drugs, but where both cohorts have a diagnosis of T2DM and heart disease.

Alternatively, you may want to develop a model to predict which patients will progress from mild T2DM to severe T2DM. This can be framed as a PLP question and could serve to flag patients at greater risk of transitioning to severe T2DM for more vigilant care.

From a purely pragmatic point of view, defining a study question also requires assessing whether the approaches required to answer a question conforms to available functionality within the OHDSI tool set (see Chapter 7 for a detailed discussion of question types that can addressed with current tool). Of course it is always possible to design your own analytic tools or modify those currently available to answer other questions.

19.2.2 Review Data Availability and Quality

Before committing to a particular study question, it is recommended to review the quality of the data (see Chapter 15) and really understand the nature of your particular observational healthcare database in terms of which fields are populated and what care settings the data covers. This can help to quickly identify issues that may make a study question infeasible in a particular database. Below, we point out some common issues that may arise.

Let’s return to the example above of developing a predictive model for progression from mild T2DM to severe T2DM. Ideally severity of T2DM might be assessed by examining glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) levels which is a lab measurement that reflects a patient’s blood sugar levels averaged over the prior 3 months. These values may or may not be available for all patients. If unavailable for all or even a portion of patients, you will have to consider whether other clinical criteria for severity of T2DM can be identified and used instead. Alternatively, if the HbA1c values are available for only a subset of patients, you will also need to evaluate whether focusing on this subset of patients only would lead to unwanted bias in the study. See Chapter 7 for additional discussion of the issue of missing data.

Another common issue is the lack of information about a particular care setting. In the PLE example described above, the suggested outcome was hospitalization for heart failure. If a given database does not have any inpatient information, one may need to consider a different outcome to evaluate the comparative effectiveness of different T2DM treatment approaches. In other databases, outpatient diagnosis data may not be available and therefore one would need to consider the design of the cohort.

19.2.3 Study Populations

Defining a study population or populations is a fundamental step of any study. In observational research, a group of individuals that is representative of the study population of interest is often referred to as a cohort. The required patient characteristics for selection into a cohort will be determined by the study population that is relevant for the clinical question at hand. An example of a simple cohort would be patients older than 18 years of age AND with a diagnosis code for T2DM in their medical record. This cohort definition has two criteria connected by AND logic. Often cohort definitions contain many more criteria which are connected by more complex, nested boolean logic and additional temporal criteria such as specific study periods or required lengths of time for a patient’s baseline period.

A refined set of cohort definitions requires the review of appropriate scientific literature and advice from clinical and technical experts who understand some of the challenges in interpreting your specific database to identify appropriate groups of patients. It’s important to keep in mind when working with observational data that these data do not provide a complete picture of a patient’s medical history, but rather a snapshot in time whose fidelity is subject to both human error and bias that may have been introduced in recording of the information. A given patient may only be followed for a finite time referred to as their observation period. For a given database or care setting and disease or treatment under study, a clinical researcher may be able to make suggestions to avoid the most common sources of error. To give a straightforward example, a common issue in identifying patients with T2DM is that T1DM patients are sometimes mistakenly coded with a diagnosis of T2DM. Because patients with T1DM are fundamentally a different group, the unintentional inclusion of a group of T1DM patients in a study intended to examine T2DM patients could skew the results. In order to have a robust definition of a T2DM cohort, one may want to eliminate patients who have only ever been prescribed insulin as a diabetes treatment to avoid having patients with T1DM erroneously represented. At the same time, however, there may also be situations where one is simply interested in the characteristics of all patients who have a T2DM diagnosis code in their medical record. In this case, it may not be appropriate to apply further qualifying criteria to attempt to remove erroneously coded T1DM patients.

Once the definition of a study population or populations is described, the OHDSI tool ATLAS is a good starting point to create the relevant cohorts. ATLAS and the cohort generation process are described in detail in Chapters 8 and 10. Briefly, ATLAS provides a user interface (UI) to define and generate cohorts with detailed inclusion criteria. Once cohorts are defined in ATLAS, a user can directly export their detailed definitions in a human-readable format for incorporation in a protocol. If for some reason an ATLAS instance is not connected to an observational health database, ATLAS can still be used to create a cohort definition and directly export the underlying SQL code for incorporation into a study package to be run separately on a SQL database server. Directly using ATLAS is recommended when possible because ATLAS provides some advantages above and beyond the creation of SQL code for the cohort definition (see below). Finally, there may be some rare situations where a cohort definition can not be implemented with the ATLAS UI and requires manual custom SQL code.

The ATLAS UI enables defining cohorts based on numerous selection criteria. Criteria for cohort entry and exit as well as baseline criteria can be defined on the basis of any domains of the OMOP CDM such as conditions, drugs, procedures, etc. where standard codes must be specified for each domain. In addition, logical filters on the basis of these domains, as well as time-based filters to define study periods, and baseline timeframes can be defined within ATLAS. ATLAS can be particularly helpful when selecting codes for each criteria. ATLAS incorporates a vocabulary-browsing feature which can be used to build sets of codes required for your cohort definitions. This feature relies solely on the OMOP standard vocabularies and has options to include all descendants in the vocabulary hierarchy (see Chapter 5). Note therefore that this feature requires that all codes have been appropriately mapped to standard codes during the ETL process (see Chapter 6). If the best codesets to use in your inclusion criteria are not clear, this may be a place where some exploratory analysis may be warranted in cohort definitions. Alternatively a more formal sensitivity analysis could be considered to account for different possible definitions of a cohort using different codesets.

Assuming that ATLAS is configured appropriately to connect to a database, SQL queries to generate the defined cohorts can be run directly within ATLAS. ATLAS will automatically assign each cohort a unique id which can also be used to directly reference the cohort in the backend database for future use. The cohort may be directly used within ATLAS to run an incidence rate study or it may be pointed to directly in the backend database by code in a PLE or PLP study package. For a given cohort, ATLAS saves only the patient ids, index dates and cohort exit dates of the individuals in the cohorts. This information is sufficient to derive all the other attributes or covariates that may be needed for the patients such as patient’s baseline covariates for a characterization, PLE or PLP study.

When a cohort is created, summary characteristics of the patient demographics and frequencies of the most frequent drugs and conditions observed can be created and viewed by default directly within ATLAS.

In reality, most studies require specifying multiple cohorts or multiple sets of cohorts which are then compared in various ways to gain new clinical insights. For PLE and PLP, the OHDSI tools provide a structured framework to define these multiple cohorts. For example, in a PLE comparative effectiveness study, you will typically define at least 3 cohorts, a target cohort, a comparator and an outcome cohort (see Chapter 12). In addition, to run a full PLE comparative effectiveness study, you will also need a number of cohorts with negative control outcomes and positive control outcomes. The OHDSI toolset provides ways to help speed and in some cases automate the generation of these negative and positive control cohorts as discussed in detail in Chapter 18.

As a final note, defining cohorts for a study may benefit from ongoing work in the OHDSI community to define a library of robust and validated phenotypes where a phenotype is essentially an exportable cohort definition. If any of these existing cohort definitions are appropriate for your study, the exact definitions can be obtained by import of a json file into your ATLAS instance.

19.2.4 Feasibility and Diagnostics

Once cohorts are defined and generated, a more formal process to examine study feasibility in available data sources can be undertaken and the findings summarized in the finalized protocol. An evaluation of study feasibility can encompass a number of exploratory and sometimes iterative activities. We describe a few common aspects here.

A primary activity at this stage will be to thoroughly review the distributions of characteristics within your cohorts to ensure that the cohort you generated is consistent with the desired clinical characteristics and flag any unexpected characteristics. Returning to our T2DM example above, by characterizing this simple T2DM cohort by reviewing the frequencies of all other diagnoses received, one may be able to flag the issue of also capturing patients with T1DM or other unanticipated issues. It is good practice to build such a step of initially characterizing any new cohort into the study protocol as a quality check of clinical validity of the cohort definition. In terms of implementation, the easiest way to perform a first pass at this will be to examine the cohort demographics and top drugs and conditions that can be generated by default when a cohort is created in ATLAS. If the option to create the cohorts directly within ATLAS is not available, manual SQL or use of the R feature extraction package can be used to characterize a cohort. In practice, in a larger PLE study or PLP study, these steps can be built into the study package with feature extraction steps.

Another common and important step to assess feasibility for a PLE or PLP is an assessment of cohort sizes and the counts of outcomes in the target and comparator cohorts. The incidence rate feature of ATLAS can be used to find these counts which can be used to perform power calculations as described elsewhere.

Another option which is highly recommended for a PLE study is to complete the propensity score (PS) matching steps and relevant diagnostics to ensure that there is sufficient overlap between the populations in the target and comparator groups. These steps are described in detail in Chapter 12. In addition, using these final matched cohorts, the statistical power can then be calculated.

In some cases, work in the OHDSI community examines the statistical power only after a study is run by reporting a minimal detectable relative risk (MDRR) given the available sample sizes. This approach may be more useful when running high throughput, automated studies across a lot of databases and sites. In this scenario, a study’s power in any given database is perhaps better explored after the all analyses have been performed rather than pre-filtering.

19.2.5 Finalize Protocol and Study Package

Once the legwork for all the previous steps has been completed, a final protocol should be assembled that includes detailed cohort definitions and study design information ideally exported from ATLAS. In Appendix D, we provide a sample table of contents for a full protocol for a PLE study. This can also be found on the OHDSI github. We provide this sample as a comprehensive guide and checklist, but note some sections may or may not be relevant for your study.

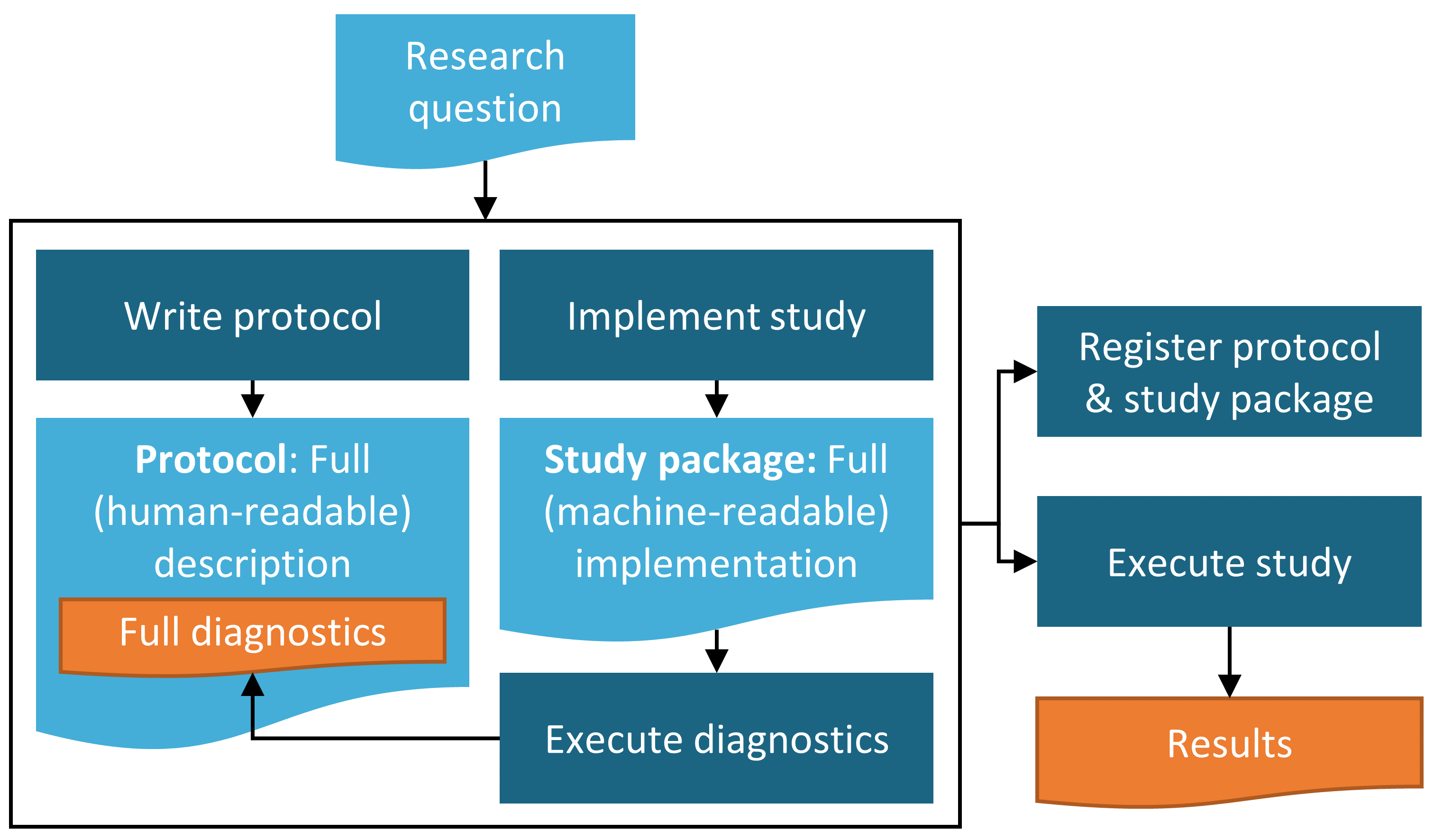

As shown in Figure 19.1, assembling the final study protocol in human-readable form should be performed in parallel with preparing all the machine-readable study code that is incorporated into the final study package. These latter steps are referred to as study implementation in the diagram below. This will include export of the finalized study package from ATLAS and/or development of any custom code that may be required.

The completed study package can then be used to execute only the preliminary diagnostics steps which in turn can be described in the protocol. For example, in the case of a new user cohort PLE study to examine comparative effectiveness of two treatments, the preliminary execution of study diagnostics steps will require cohort creation, propensity score creation, and matching to confirm that the target and comparator populations have sufficient overlap for the study to be feasible. Once this is determined, power calculations can be performed with the matched target and comparator cohorts intersected with the outcome cohort to obtain outcome counts and the results of these calculations can be described in the protocol. On the basis of these diagnostics results, a decision can then be made whether or not to move forward with executing the final outcome model. In the context of a characterization or a PLP study, there may be similar steps that need to be completed at this stage, although we don’t attempt to outline all scenarios here.

Importantly, we recommend at this stage to have your finalized protocol reviewed by clinical collaborators and stakeholders.

Figure 19.1: Diagram of the study process.

19.2.6 Execute Study

Once all prior steps have been completed, study execution should ideally be straightforward. Of course, the code or process should be reviewed for fidelity to the methods and parameters outlined in the protocol. It may also be necessary to test and debug a study package to ensure it runs appropriately in your environment.

19.2.7 Interpretation and Write-Up

In a well-defined study where sample sizes are sufficient and data quality is reasonable, the interpretation of results will often be straightforward. Similarly, because most of the work of creating a final report other than writing up the final results is done in the planning and creation of the protocol, the final write-up of a report or manuscript for publication will often be straightforward as well.

There are, however, some common situations where interpretation becomes more challenging and should be approached with caution.

- Sample sizes are borderline for significance and confidence intervals become large

- Specific for PLE: p-value calibration with negative controls may reveal substantial bias

- Unanticipated data quality issues come to light during the process of running the study

For any given study, it will be up to the discretion of the study authors to report on any concerns above and temper their interpretation of study results accordingly. As with the protocol development process, we also recommend that the study findings and interpretations be reviewed by clinical experts and stakeholders prior to releasing a final report or submitting a manuscript for publication.

19.3 Summary

- Study should examine a well-defined question.

- Perform appropriate checks of data quality, completeness and relevance in advance.

- Recommend to include source database expert in protocol development process if possible.

- Document proposed study in a protocol ahead of time.

- Generate study package code in parallel with written protocol and perform and describe any feasibility and diagnostics prior to executing the final study.

- Study should be registered and approved (if required) ahead of study execution.

- Finalized report or manuscript should be reviewed by clinical experts and other stakeholders.